Come. Walk with me along this pathway. It has so many interesting features for viewing – it’s worth a moment of your time. It is rather narrow, so we probably will need to walk single file or the canebrakes and other herbage will strike our arms and mark our legs. You see, these are old buffalo trails that marked the wanderings of the animal out of the grasslands of Illinois and Tennessee into the lush environment of the new Kentucky territory. The migratory animal pounded the surface of the fields, traveling from one stream to another while licking the saline grounds and seeking Kentucky’s abundant mineral waters. The “trace,” as this trail is called, is a dirt surface from years of traveling herds. It will lead us to a stream or a salt lick if we continue. Meanwhile, enjoy the giant oaks, the coveted elms and favored hickory trees in the setting. We may even be lucky enough to see some deer and other wildlife on the trace.

These imaginary trails just taken were the early roads of initial explorers and settlers of this new land. The hunters, on arrival, found not only an abundance of animals for survival and use, but neat pathways made by buffalo roaming and enhanced by Indian travel. First it was foot trails, along with equine tromping, next the small wheeled carriages, then finally the covered wagon. By then, the state’s road system was clearly defined for travelers. With convenient roads, the people came, the communities grew and the need to travel among the different locations gave rise to the early taxi service called the stagecoaches. There is no more colorful age of history of our state than the era of this public travel.

The wagon trails were not in the best shape, often having been washed out by wind, rains and heavy traffic. Attempts were made to improve them by local efforts and attempts by the General Assembly of Kentucky in the large population area around Lexington and the Bluegrass lands. According to the season, either dust or muddy rutting of the roads made travel difficult. Nevertheless, wagon-road travel became more frequent, increasing the population of the state. Post-riders provided news to and from the different districts, inspired trade between the communities and increased travel by individuals between the settlements. As a result, the stagecoach services made their appearance.

John Kennedy, a Lexington gentleman, established the first stagecoach service in the Kentucky commonwealth on Wednesday August 9, 1803. The service ran from Lexington to Winchester, on to Mt. Sterling and finally to Olympian Springs, a popular mineral springs resort in Montgomery County. By leaving Lexington at four o’clock in the morning, the service traveled the approximately 47 miles, arriving at the end of the trip the same day. The trip made stops in the four mentioned cities where stage managers in each town handled the exiting of or greeting of new riders and drivers. The needs of the team of horses were managed by the stock tenders. The initial service was well designed, listing the cost of a seat in the stagecoach depending on where you joined the trip. Even the cost of baggage and the limit on amount allowed for each customer were listed in their notices. The coach service was so successful, a new trip from Lexington to Frankfort was soon established.

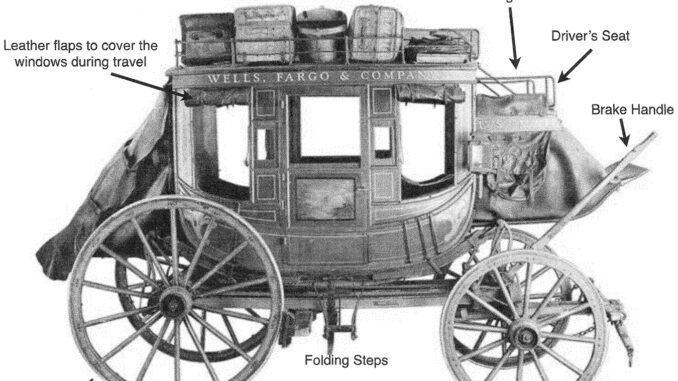

The comfort of a seat and services provided along the trip were preferred by most people compared to walking or riding horseback. The stage travel, though desired, was not always so pleasant. The first stagecoaches were not that comfortable. One entered the early-style carrier by the front entrance, no side doors. The entire inside consisted of flat benches with no back rest. One climbed over the bench to reach their seat and placed their baggage under their seat. The roadway traveled did not add comfort to the rider. The wagon-roads were still rough surfaces that bounced the rider back and forth and often up toward the ceiling.

The stage had no windows, of course… only leather strips to help keep the rain out and limit the undesirable dust and heat from the roadway. Often the wagon-roads were muddy, so riders would have to descend and walk around a muddy quagmire to prevent the wheels getting stuck or a disaster occurring. Using the same narrow passageways, a team of pack-horse men, who were not pleased with the new ways of carrying people and merchandise, often created a problem, refusing to go in a ditch to let the stage go by. Early means of travel by stagecoach experienced many challenges in its conception but the value of the service for travelers continued to expand. From 1803 to 1850, travel connecting with Cinncinnati, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Washington centers became routine yet cosmopolitan.

Meanwhile, during the first half of the 1800s, Southern Kentuckians were experiencing related growth in connection with other communities. Merchants had already made connection in sending products and merchandise to the major northern cities and southern ports. Postal service and the latest headlines were being received through the Louisville, Nashville, and Lexington post riders. Either by wheel transport or horseback travel, the communities welcomed the usual once-a-week blast of the rider’s horn. Folks joyously welcomed the mail, the newspapers and gossip from distant regions.

Bowling Green benefitted greatly by the establishment of the Louisville-Nashville Turnpike, also known as the Telford Road, in the 1820s. The road ran from Louisville, through Elizabethtown, Munfordville, Bowling Green and Franklin, crossing the Salt River at West Point, the Green River at Munfordville, the Barren River at Bowling Green, and the Cumberland River at Nashville. All crossings were by ferry service charge, according to Col. H.A. Sommers of Elizabethtown, a former stagecoach driver for years on the new turnpike. He described the turnpike as well built, “much like the old Appian Way out of Rome. The first course was large stone put in piece by hand, over which the second layer of smaller stone was laid. It is the old base that the present highway, known as the Dixie Highway, and to tourists as U.S. 31, was built.” As with most state roads in Kentucky, they were maintained by money taken in by toll gates.

Col. Sommers says the trip from Louisville to Nashville took two days and a night at a speed of eight miles an hour. The coaching line maintained a stable about every eight or nine miles along the turnpike to be used in emergencies. The Colonel discusses the various taverns and homes that served as eating and/or resting places along the trip, especially mentioning Bell’s Tavern at the Glasgow Junction which was the destination of many riders visiting Mammoth Cave. Just as memorable is the Old Stagecoach Stop built in 1841 eight miles east on U.S. 31W by Samuel Murdrell. A historical marker marks the spot on the side of the road at its location.

The Louisville-Nashville Turnpike stage lines were abandoned before January 1, 1860, being replaced by the L&N railroad – a sad day in a colorful history of our state.

The facts, the folklore, the trials and tribulations of this great era of stagecoach life will always capture our thoughts, our hearts, the literature and film world. Thankfully, there is a wealth of information available.

-by Mary Alice Oliver

About the Author: Mary Alice Oliver is a Bowling Green native who is a 1950 graduate of Bowling Green High School. She retired from Warren County Schools after 40 years in education. Visiting familiar sites, researching historical records and sharing memories with friends are her passions.